Foundations

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What best practice and generic skills underpin you encounters with software skills?

Objectives

Use best practice in using software and data

Recognize need for best practice

Foundations

Before we crack on with using the computational tools at our disposal, I want to spend some time on some foundation level stuff - a combination of best practice and generic skills that frame what you’ll encounter across Library Carpentry.

The Computer is inflexible

This does not mean that the computer isn’t useful. Given a repetitive task, an enumerative task, or a task that relies on memory, it can produce results faster, more accurately, and less grudgingly than you or I. But the computer only does what you tell it to. In most cases, when we get errors, it means that we did not give the computer enough information or that the computer failed to interpret what you mean because it can only work with what it knows (ergo, it is bad at interpreting). Error messages can be frustrating, and many times the information in them is archaic and incomprehensible. Many times, though, error messages give us important information to understand what we need to change so that the computer will understand what we want it to do.

Why take an automated or computational approach

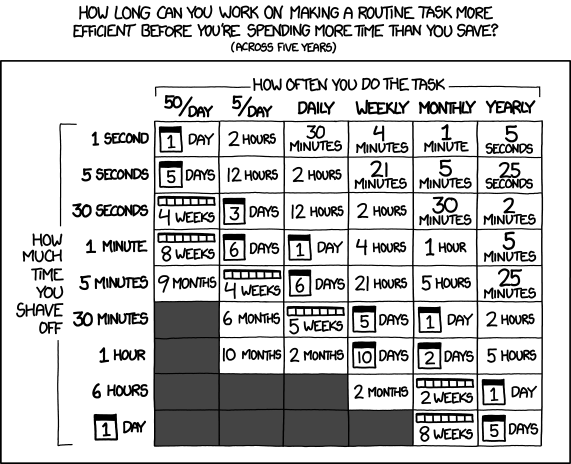

Otherwise known as the ‘why not do it manually?’ question. If you know you’ll need to repeat a task, you should consider automating it. Many times the main barrier that we have against automating a task is not knowing how to do it, so in this lesson we are going to work on some tools to automate tasks. Figuring out how much time to devote to automating a task is also a skill worth learning.

How to decide whether to automate or not?: see Is it worth the time? image from xkcd.com.

This is one of the main areas in which programmatic ways of doing outside of IT service environments are changing library practice. Andromeda Yelton, a US based librarian closely involved in the Code4Lib movement, put together an American Library Association Library Technology Report called “Coding for Librarians: Learning by Example.” The report is pitched at a real world relevance level, and in it Andromeda describes scenarios library professionals told her about where learning a little programming, usually learning ad-hoc, had made a difference to their work, to the work of their colleagues, and to the work of their library.

Main lessons:

- Borrow, Borrow, and Borrow again. This is a mainstay of programming and a practice common to all skill levels, from professional programmers to people like us hacking around in libraries;

- The correct language to learn is the one that works in your local context. There truly isn’t a best language, just languages with different strengths and weaknesses, all of which incorporate the same fundamental principles;

- Consider the role of programming in professional development. That is both yours and of those you manage;

- Knowing (even a little) code helps you evaluate projects that use code. Programming can seem alien. Knowing some code makes you better at judging the quality of software development or planning activity that include software development

- Automate to make the time to do something else! Taking the time to gather together even the most simple programming skills can save time to do more interesting stuff! (even if often that more interesting stuff is learning more programming skills …)

Plain text formats are your friend

Why? Because computers can process them!

If you want computers to be able to process your stuff, try to get in the habit where possible of using platform-agnostic formats such as .txt for notes and .csv or .tsv for tabulated data (the latter pair are just spreadsheet formats, separated by commas and tabs respectively). These plain text formats are preferable to the proprietary formats used as defaults by Microsoft Office because they can be opened by many software packages and have a strong chance of remaining viewable and editable in the future. Most standard office suites include the option to save files in .txt, .csv and .tsv formats, meaning you can continue to work with familiar software and still take appropriate action to make your work accessible. Compared to .doc or .xls, these formats have the additional benefit of containing only machine-readable elements. Whilst using bold, italics, and colouring to signify headings or to make a visual connection between data elements is common practice, these display-orientated annotations are not (easily) machine-readable and hence can neither be queried and searched nor are appropriate for large quantities of information (the rule of thumb is if you can’t find it by CTRL+F it isn’t machine readable). Preferable are simple notation schemes such as using a double-asterisk or three hashes to represent a data feature: in my own notes, for example, three question marks indicate something I need to follow up on, chosen because ??? can easily be found with a CTRL+F search.

??? was also chosen by me because it doesn’t clash with existing schemes. Though it is likely that notation schemes will emerge from existing individual practice, existing schema are available to represent headers, breaks, et al. One such scheme is Markdown, a lightweight markup language. Markdown files are named as .md, are machine readable, human readable, and used in many contexts - GitHub for example, renders text via Markdown. An excellent Markdown cheat sheet is available on GitHub for those who wish to follow – or adapt – this existing schema. Notepad++ http://notepad-plus-plus.org/ is recommended for Windows users as a tool to write Markdown text in, though it is by no means essential for working with .md files. Mac or Unix users may find Komodo Edit, Text Wrangler, Kate, or Atom helpful. Combined with pandoc, a Markdown file can be exported to PDF, HTML, a formatted Word document, LaTeX or other formats, so it is a great way to create machine-readable, easily searchable documents that can be repurposed in many ways. It is a universal document converter.

Naming files sensible things is good for you and for your computers

Working with data is made easier by structuring your stuff in a consistent and predictable manner.

Why?

Without structured information, our lives would be much poorer. As library and archive people we know this. But I’ll linger on this a little longer because for working with data it is especially important.

Examining URLs is a good way of thinking about why structuring research data in a consistent and predictable manner might be useful in your work. Good URLs represent with clarity the content of the page they identify, either by containing semantic elements or by using a single data element found across a set or majority of pages.

A typical example of the former are the URLs used by news websites or blogging services. WordPress URLs follow the format:

ROOT/YYYY/MM/DD/words-of-title-separated-by-hyphens- http://cradledincaricature.com/2015/07/24/code-control-and-making-the-argument-in-the-humanities/

A similar style is used by news agencies such as a The Guardian newspaper:

ROOT/SUB_ROOT/YYYY/MMM/DD/words-describing-content-separated-by-hyphens- http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/feb/20/rebekah-brooks-rupert-murdoch-phone-hacking-trial

In data repositories, URLs structured by a single data element are often used. The NLA’s TROVE structures its online archive using the format:

ROOT/record-type/REF- http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/6315568

And the Old Bailey Online uses the format:

- ROOT/browse.jsp?ref=REF`

- http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?ref=OA16780417

What we learn from these examples is that a combination of semantic description and data elements make for consistent and predictable data structures that are readable both by humans and machines. Transferring this kind of pattern to your own files makes it easier to browse, to search, and to query using both the standard tools provided by operating systems and by the more advanced tools Library Carpentry will cover.

In practice, the structure of a good archive might look something like this:

- A base or root directory, perhaps called ‘work’.

- A series of sub-directories such as ‘events’, ‘data’, ‘ projects’ et cetera

- Within these directories are series of directories for each event, dataset or project. Introducing a naming convention here that includes a date element keeps the information organised without the need for subdirectories by, say, year or month.

All this should help you remember something you were working on when you come back to it later (call it real world preservation).

The crucial bit for our purposes, however, is the file naming convention you choose. The name of a file is important to ensuring it and its contents are easy to identify. ‘Data.xslx’ doesn’t fulfil this purpose. A title that describes the data does. And adding dating convention to the file name, associating derived data with base data through file names, and using directory structures to aid comprehension strengthens those connection.

An example of a file naming convention that you could use for your data is

project_datatype_location_yyyy-mm-dd.ext

In this example, you are including information about the project, the kind of data you have in this file (for example, interviews), the location associated with this data (for example, for the subset of your interviews that took place in Oregon), and the date. Using standards to name your files is also a good idea. For example, if you are adding the name of countries for location, use the standardized codes from ISO 3166-1.

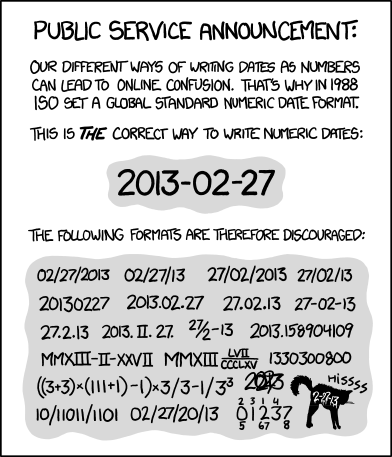

The way you refer to dates in your own documents and data is one of the most useful areas where to use a standard. Using the ISO 8601 standard will make your dates consistent, and will also allow your computer to organize your documents by date automatically.

Why use a standard for your dates?: see ISO 8601 image from xkcd.com.

Key Points

Data structures should be consistent and predictable

Consider using semantic elements or data identifiers to data directories

Fit and adapt your data structure to your work

Apply naming conventions to directories and file names to identify them, to create associations between data elements, and to assist with the long term readability and comprehension of your data structures